Registering for Trademark Protection in China

A seller seeking to protect their trademarks in China has two options: (1) to register under the international agreement the “Madrid Protocol” or (2) to register in China itself with the Chinese Trademark Office (“CTMO”). Both options will give the Seller trademark protection for their product; however, there is a difference as to the ease and effectiveness of these methods. Generally speaking, registering under the Madrid Protocol is easier while registering with the CTMO may give the Seller an edge in any future trademark disputes that may arise in China.

(A) Trademark Registration Via the Madrid Protocol

The Madrid System is an international agreement that allows persons to register their trademarks under different nation’s trademark systems through a single and standardized system. The allure of the Madrid System for the Seller looking to enter the Chinese marketplace is that the registration process can entirely be done from home on the easy-to-use English-language website at http://www.wipo.int/madrid/en/.

Anthony’s Advice: For Sellers with a smaller operation or a non-Chinese speaking Seller, the Madrid Protocol offers a quick and practical alternative to filing trademark applications with the Chinese Trademark Office.

Breakdown of Madrid Protocol Trademark Registration

- Eligibility – registration under the Madrid Protocol merely requires that the Seller be a citizen of one of the 116 nations covered by the agreement. Checking eligibility should be the first step in the Seller’s process to registration.

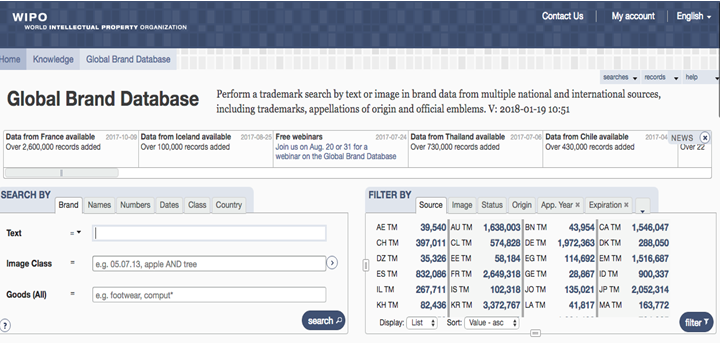

- Brand Search – the WIPO website provides a user-friendly tool to search their international database of registered trademarks. The Seller should use this to preempt and prevent any future issues that could arise.[1]

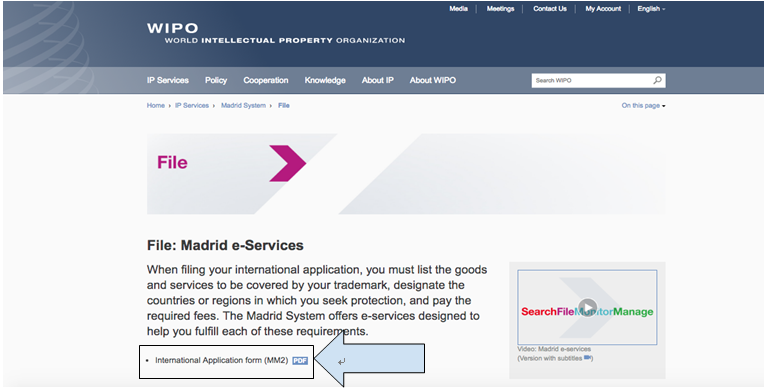

- Filing – the WIPO website provides a link to the 11-page registration document to file for an international trademark application. [2]

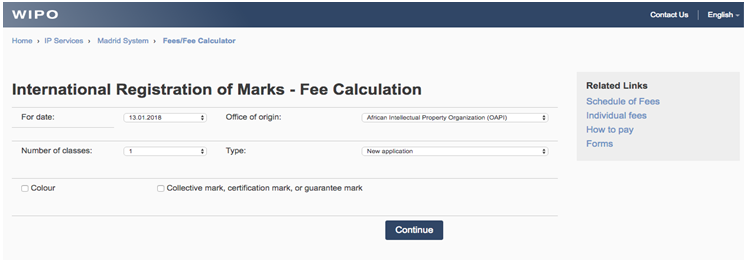

- Cost – registration costs 653 Swiss Francs (approx. 679 USD) + country cost + nature of the mark + number of classes registered for. The website features a cost-calculator that a Seller can use even before registration begins to decide whether or not they wish to seek trademark protection.[3]

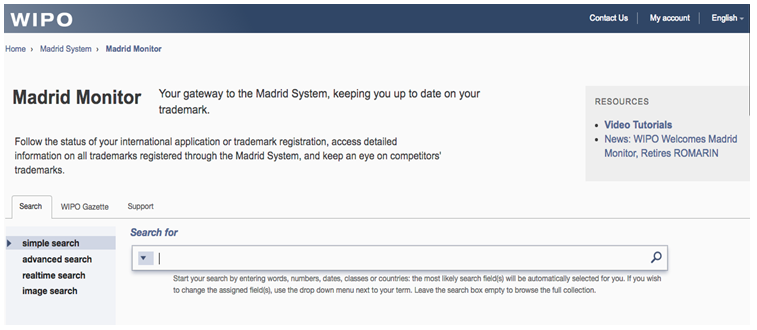

- Monitoring – After the trademark application has been filed, the WIPO offers a useful monitoring tool for the Seller to watch their application as it moves along the approval process. It also gives the Seller the ability to monitor other similar trademark applications that may potentially be competing with theirs.[4]

- Managing – finally, after a Seller’s application has been approved and registered as a trademark, sellers have the ability to monitor their trademark and tailor it with their changing business needs.

Reality of the Madrid Protocol

While the Madrid Protocol may appear simple, it is by no means a perfect system. The greatest flaw with choosing to go this route for the registration of a trademark is that the WIPO, rather than the Seller him or herself, files the trademark application with the CTMO. The CTMO then reviews the application for approximately eleven months. During this time, the Seller will have no contact with the CTMO. Therefore, if a trademark is not approved by the CTMO, the applicant will only discover this until after that roughly eleven-month period when the CTMO informs the WIPO, and the WIPO then informs you, that your trademark application has been denied.

This system leaves the Seller without the ability to correct their application during the approval process while their application is with the CTMO. If denied by the CTMO, then the Seller’s only option is to appeal this decision and file for an application review with the Trademark Review and Adjudication Board (“TRAB”).

(B) Trademark Registration Via the CTMO

A Seller may choose to register their trademark domestically with the CTMO. While not as “one size fits all” as an application via the Madrid Protocol, registering directly with the CTMO has its advantages.

(1) Registration via CTMO is faster. Registration via the CTMO renders a decision within nine months of filing.[5] Registration under the Madrid Protocol takes twelve to eighteen months.[6]

(2) Registration via CTMO may be “safer.” On top of registration being simply faster with the CTMO, it is also, in a way, more secure. If a seller chooses to file via the Madrid Protocol, “it is not unusual that the CTMO does not input right away into its system the data received from WIPO about international trademark extensions.”[7] This means, that an internationally-submitted trademark application could potentially be filed after a domestically-submitted trademark application. That domestic application would then be approved, registered, and begun to sell products under that trademark before the WIPO trademark, that was submitted first, had a chance to be registered. Therefore, despite China being a “first to file” district, the domestically-filed application may have the upper hand in a trademark dispute with the international-registrant who submitted their application first.

CJ’s Summary: When you file with the CTMO, your application is both approved more quickly and filed directly with the source. Even though a Madrid Protocol application may be simpler, it puts a middleman between sellers and the people reading your application. This gives the people over at the CTMO the opportunity to put internationally-filed applications on the “back burner” for a while; in the world of trademark applications, every second counts.

Breakdown of a CTMO Trademark Registration

As a warning to the Seller looking to file their application with the CTMO, it is strongly recommended that the Seller seeks legal advice from attorneys experienced in Chinese trademark application. In addition to the application being in Mandarin, a trademark application may be rejected for a series of cultural reasons. Because of that, there are many products that would be approved and many other countries but not in China because of China-specific aversion to such trademarks for cultural reasons.

CJ’s Side Note: A Chinese trademark application is equal parts legal jargon and Chinese culture. If you are looking to file for trademark protection in China, we strongly recommend you seek experienced legal help.

Trademark law in China is governed by the Chinese Trademark Office. First and foremost, when a Seller is seeking to register their trademark in China they must first determine the “class of goods” that their product is, in accordance with Article 19 of the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China.[8] The Chinese trademark office has an extremely wide range of good classifications; thirty-four in total.[9] Some examples of these categories are: chemicals, paints, laundry items, industrial oils, pharmaceutical tools, common metals, machine tools, hand tools, surgical equipment, lighting apparatus, vehicles, firearms, musical instruments, etc. Each category, furthermore, has sub-categories that must be properly selected. A Seller’s failure to select the proper classification for their product they are seeking trademark protection for can result in an automatic rejection of said trademark.

Even after successfully filing a trademark application under the proper goods-category and subcategory, the application process is not over. Those inspecting a trademark application at the CTMO will be looking for any one of the eight possible reasons to reject a trademark application under Article 10 of the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China. Reasons for rejection of an application are:

- Identical or similar to a Chinese state name, national symbol, flag, emblem etc;

- Identical or similar to a foreign nation’s state name, national symbol, flag, emblem etc;

- Identical or similar to an international bodies’ name, national symbol, flag, emblem etc;

- Identical or similar to official signs and hallmarks;

- Identical or similar to the symbols or names of the Red Cross or the Red Crescent;

- Those having the nature of discriminating against any nationality;

- Those having nature or exaggeration and fraud in the advertised goods;

- Those detrimental to socialist morals or customs or having other unhealthy influences.[10]

Sections 1-8 of Article 10 clearly give the CTMO a wide range of discretion when analyzing a trademark application. No section gives a wider, and potentially more confusing, range of discretion than section 8, which says that a trademark may be rejected for having “unhealthy influences” on Chinese society.[11] While other nations such as the UK, Germany, and Japan have similar provisions in their trademark laws, none of those nations are socialist countries or steeped in the particularly unique Chinese cultural history. Because of this, it is very easy for a trademark applicant to inadvertently offend socialist or cultural ideals in the eyes of the CTMO. Furthermore, the CTMO does not need to provide any proof or concrete examples of actually how your trademark application would have negatively influenced the people of China.[12] Whether the Seller meant to offend or negatively influence a group of people within China is irrelevant. If the CTMO feels that your trademark application does that in some way, they will reject your trademark application.

Anthony’s Breakdown: Section 8 is purposely broad and vague. It allows the CTMO to have the ability to reject your trademark application for a seemingly endless range of reasons and to do so at their own discretion with no proof. Practice makes perfect with filing a trademark application; any Seller looking to do this should seek out attorneys both with experience in filing these applications and an understanding of Chinese culture.

If an application is rejected by the CTMO, the applicant has the ability to file an appeal with the Trademark Review Adjudication Board (“TRAB”). This book will cover more on this topic later in chapter five, but in essence, the applicant must successfully-allege to the board that the objectionable portion of their application won’t be realized by the Chinese people.

[1]Global Brand Database, WIPO World Intellectual Property Organization (last visited Jun. 19, 2018), http://www.wipo.int/branddb/en/.

[2]File: Madrid e-Services, WIPO World Intellectual Property Organization (last visited Jun. 19, 2018), http://www.wipo.int/madrid/en/file/.

[3]International Registration of Marks – Fee Calculation, WIPO World Intellectual Property Organization (last visited Jun. 19, 2018), http://www.wipo.int/madrid/en/fees/calculator.jsp.

[4]IMadrid Monitor, WIPO World Intellectual Property Organization (last visited Jun. 19, 2018), http://www.wipo.int/madrid/monitor/en/index.jsp.

[5]Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China, ch. II, art. 24 – ch. III, art. 30.

[6]Summary of Madrid Agreement Concerning the International, WIPO World Intellectual Property Organization (last visited Jun. 19, 2018), http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/registration/madrid/summary_madrid_marks.html.

[7]WanhuidaPeksung, How to File? Directly in China with the CTMO or Through International Extension to China?, Wan Hu Dai Intellectual Property Express, No. 32 (Jul. 2016 Issue), http://www.managingip.com/Article/3669018/How-to-file-Directly-in-China-with-the-CTMO-or-through-international-extension-to-China.html..

[8]Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China, ch. II, art. 19 (Aug. 30, 2013).

[9]Trademark Classifications List of Goods and Services, Chinese Trademark Office (last visited Jun. 19, 2018), https://www.chinatrademarkoffice.com/blog/show/190.html.

[10]Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China, ch. II, art. 10 (Aug. 30, 2013).

[11]Id.

[12] Wang Ze, Zhou Yunchuan, Zhou Bo, Rui Songyan and Xu Lin, Landmark Trademark Cases in China: An In-Depth Analysis, 61.

Author Bio:

This article was researched and written by CJ Rosenbaum, Esq., a founding partner of Rosenbaum Famularo, P.C., the law firm behind AmazonSellersLawyer.com and two incredible law students who participated in the firm’s Summer Associate Program: Conor Wiggins and Moshe Allweiss. Conor and Moshe are 2019 J.D. Candidates at the Hofstra University School of Law. For a more thorough explanation of Chinese Intellectual Property Law for Sellers, please request a copy of our book, Amazon Sellers’ Guide to Chinese Intellectual Property Law.